Ask any Cambodian about Queen Jayarājadevī and he will tell you that Jayavarman VII married her first, and, when she died, married her sister Indradevī.

But George Coedès wrote that when Jayarājadevī died, Jayavarman VII elevated her sister Indradevī, a lesser queen, to principal queen. Which meant that he was married to both of them at the same time.

Wait - it gets even more complicated. The inscription on the Preah Khan Stele records that Jayavarman VII married Rājendradevī first, and that she bore his first son.

This description of Jayarājadevī, written by Indradevī in the Phimeanakas inscription, has survived:

“[her] asceticism, her virtuous conduct, her tears, her likeness to Sita, found by her husband and then separated from him, her body thinned by observances, her religion, her devotion to him, her joy at his ultimate return.”

“separated from him” is believed to refer to the period when he was absent from Angkor on a military campaign against the Cham kingdom to the east, thought to be seven years. “thinned by observances” is believed to mean that she fasted excessively (she was very religious).

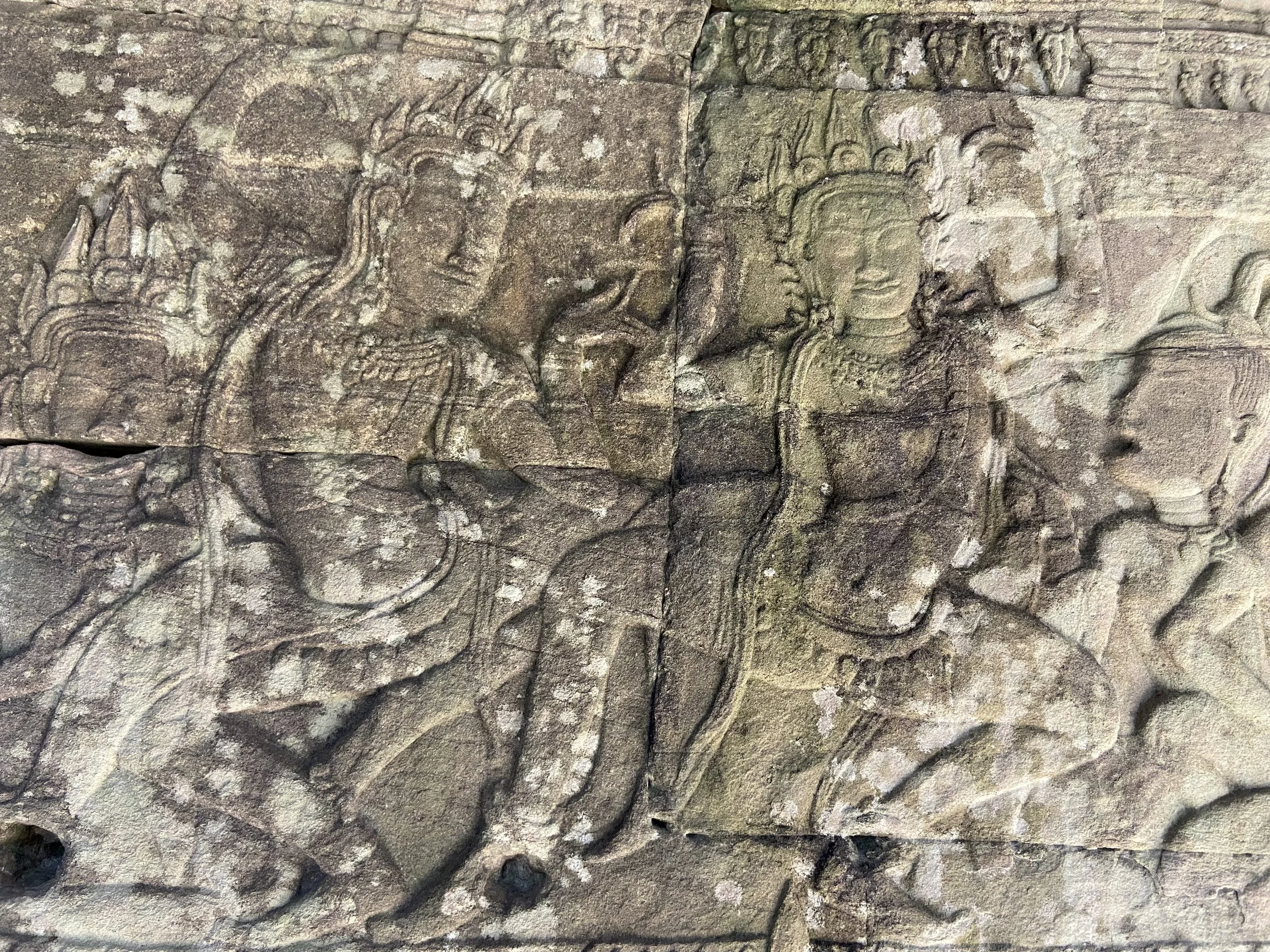

Legend tells us that she was very much in love with her husband. And that she cried a lot; in fact there is a bas relief of her at Banteay Chmar in which she appears to be crying.

By the time I learned that Jayavarman VII had married Rājendradevī first, I had already learned that the lives of many of the Angkorian queens were very sad. Because they had no control of their lives. I wondered what had happened to Jayarājadevī. This is what I believe was the sequence of events:

Before he became king, Jayavarman VII married Rājendradevī.

Rājendradevī died, and he married Jayarājadevī.

He left on the military campaign against the Cham, and it was many years until he returned.

Upon his coronation in 1181 he was required to take four more wives, so that he would have five. One of these wives was Indradevī, at Jayarājadevī’s insistence.

By 1190 Jayarājadevī knew she was dying, and asked Jayavarman VII to elevate Indradevī to principal queen. And he did so, so that she could see that it was done. That’s why we see Indradevī portrayed as the goddess Ganga in Preah Khan, and Jayarājadevī portrayed as mortal - as though Indradevī were the principal queen, and Jayarājadevī the second.

This sequence is a radical theory, but it’s the only one that makes sense. I will continue my research.

I think Jayarājadevī was put in a series of impossible situations. She was very attached to her husband, but then, he was gone for many years. She was not yet queen, and her husband was not the heir apparent; what would her status at Angkor have been? She would not be able to bear children, for her sake or for his, until he returned. And she didn't know if he would return (he might be killed in the military campaign). When he did finally return, he would have taken four other wives upon his coronation (we see five wives at the Bayon and at Ta Prohm). I think she simply did everything she could to cope, but couldn’t. And I think that’s why she died before she should have.

**********

I believe the Khmer word for ikat, hol, is from the Sanskrit and Gujarati word, paṭola. Where did the “h” come from? The “ṭ” in “paṭola” is aspirated. The shortening of the word is consistent with other loan words from Sanskrit.

**********

I believe the dance we see being performed at Angkor by both celestial apsarā and mortals was the South Indian temple dance Bharatnatyam. D. S. Sood of Archeological Survey of India, who served as the head construction engineer of Ta Prohm until his retirement, agrees. I put an analysis of the similarities of Angkorian dance to Bharatnatyam (and the differences) in Through the Eyes of a Queen. (The “Apsarā Dance” performed today for tourists is not the same dance - it was developed in the 1950’s by a member of the royal family.)

Take a look - the figure on the left is from Banteay Chhmar, and the woman on the right is a Bharatnatyam dancer in India today. Even the number of rows of bells on the ankles of each is the same!

Credit for photo of Indian dancer: Ms. Sarah Welch, own work, 2014, CC-BY-SA-4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. No changes were made.

I studied Bharatnatyam briefly in India. The uplifted toes were my first clue that the Angkorian figures were dancing Bharatnatyam. The feet are stamped on the floor to make the ankle bells ring, and the toes are lifted so that they’re not damaged in the process. You can see the uplifted toes very clearly in the apsarā at Prei Prasat (Ta Oun), below left. My next clue was that the Angkorian dancers are forming the Bharatnatyam Swan’s Beak mudrā with their hands (above left, her left hand).

Proving whether or not the dance we see at Angkor was Bharatnatyam would make an excellent research project for someone with a knowledge of Indian dance.

But, when looking at these dancers, how do you distinguish a mortal from an immortal?

Look at the Prei Prasat dancer on the left. Note the angle of her thighs. It’s impossible to dance in this position - she’s an apsarā. Compare her to the mortal dancer in the Angkor National Museum in Siem Reap - the angle of her thighs is very different. The apsarā is shown dancing on a pedestal, but the mortal dancer is shown dancing on a floor. The apsarā is shown with no musical accompaniment, but we can see musicians behind the mortal dancer.

Above left you see a pair of dancers entertaining the royals in Jayavarman VII’s palace on a wall of the Bayon. But Bharatnatyam is a temple dance; was it was really performed as entertainment? Yes. Because India was the model for so much of Angkorian culture, a look west often gives us the answer. Some of the maharajas maintained troupes of Bharatnatyam dancers to entertain palace guests as late as the 20th century.

**********

Is the small male figure next to the principal queen in the Southern Gallery of Angkor Wat not a dwarf servant, but a child? Determining that he was holding up a slingshot would prove it.

Above, accidental irony. You can see him holding up what appears to be a bull-faced slingshot, and buy the same slingshot on your way out of Angkor Wat. They’re carved in the village on the northern bank of Srah Srang; local boys still use them.

Sūryavarman II was at war with both the Cham and the Dai Viet. Security would have been a major concern, and everyone in the Procession of the Queens would have had some type of clearance. And a reason to be there. If the figure is proved to be a child, he was probably the adopted son of the principal queen.

If you’re interested in doing this research, you could start by accessing the E.f.E.O. online photo archive of Angkor Wat to try to find a photo taken years ago - when what the figure is holding would have been clearer because there was less erosion. Or, try coffee-table books - that’s where I found the photo of the boy next to the second queen clear enough so that I could see that he was holding onto her sash with one hand and taking something from her hand with the other. Clearly an adopted son.

**********

Lastly, we see the Procession of the Queens in the Southern Gallery of Angkor Wat, but we don’t know where they’re going. Or where they’re coming from. Zhou Daguan wrote that the royal processions he saw a century and a half later originated at the palace, and ended at a temple.

So many of the scenes on the walls of Angkor Wat are mythical that we forget the this one was real. Consider the logistics.

Firstly, all that food? Wouldn’t the palace kitchens have been the most logical place to prepare it?

Secondly, all but eleven people are on foot. They’re not going very far.

Thirdly, it’s been assumed that the military procession in front of the queens’ was going where the queens were going. Like the processions that Zhou Daguan saw. To a temple. And this was the most important pūjā of the year - Gangā Dussehra. Wouldn’t they be going to the most important temple? The only one large enough to accommodate the entire royal court, the generals on their elephants, and the infantrymen with them?

I believe the procession we see in Angkor Wat is going to Angkor Wat. We see them traveling west to east, toward the morning sun. A procession originating at the palace would be walking north to south, but would have to turn east to approach Angkor Wat. Yes, there’s no inscription, but I believe that Sūryavarman II thought we’d just… figure it out.