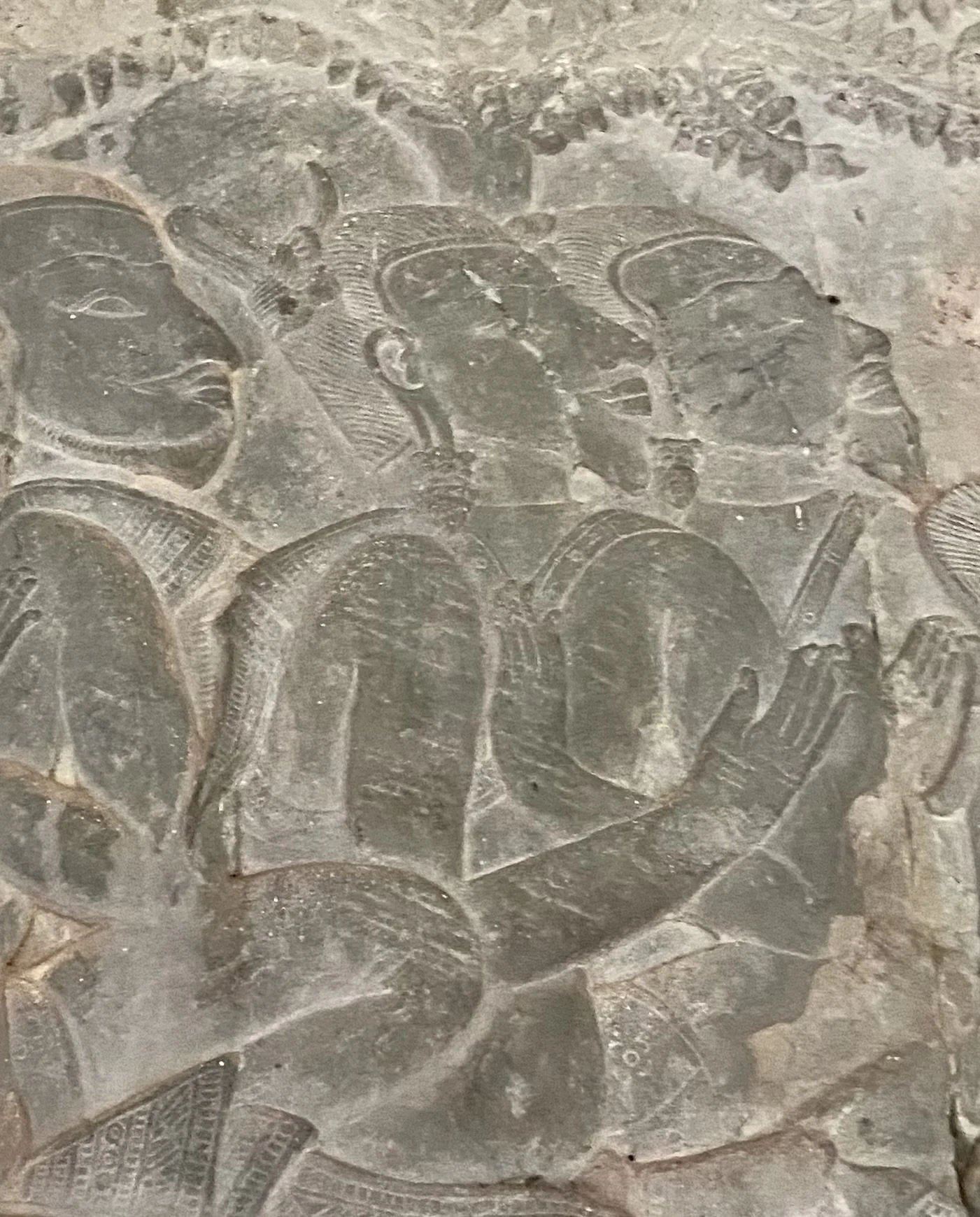

OK, who are these guys? They’re at the very end of the Procession of the Queens in the Southern Gallery of Angkor Wat.

The first description I heard was, “These are happy villagers, following the procession.” What? Suryavarman II was at war. With the Cham, and with the Dai Viet. Everyone in the Procession of the Queens would have had some type of security clearance. “Happy villagers?” Really?

Next I heard that they were men carrying rolled mats, to sit on when they’d reached the royal pūjā. I published this, because it came from a reliable source.

But a year later, I started to have second thoughts. Because security would have been so much of a concern, I knew that anyone in this procession had a reason to be there. What was theirs? I took a look at them again.

And suddenly, I remembered seeing something like what they were carrying. In an antique store. Message tubes, made into lamps. I went back to the store and asked if they had any message tubes in their original condition. They did. They told me that their stock was early-20th-century message tubes “used by the king”.

I bought one, and compared it to what the men were carrying. I thought I had a match. I thought the men were messengers.

When going through my 7,000+ photos to finish the August, 2025 edition of Through the Eyes of a Queen, I found another photo that I’d taken years before.

And there was my proof… Three men ahead of my guys, carry documents. The men carrying “rolled mats” were in fact carrying message tubes, because they were Sūryavarman II’s messengers. And look at what is around their necks. No other figures wear anything like them. Two carry small boomerang-shaped objects, in the right hand (we wouldn’t expect to see royal messages carried in the left). I think they were tubes for carrying messages over long distances. As were their necklaces. I think these men were runners.

Mystery solved? Not so fast. Had the antique store been right? Was what they’d sold me really a message tube?

In India, at the Shreyas Folk Museum in Ahmedabad, I found the Indian prototype of the Cambodian message tubes. With documents still inside.

Now, mystery solved. Many thanks to the Shreyas’ director, Dr. Hardika Raval, for sending me the photo!

Before we leave the messengers behind, look again at the giant leading them. His left arm is behind the heads of the men carrying messages. Look at his hand.

The bas relief of the Procession of the Queens was meant to be “read”, like the pages of a book. It’s loaded with information. With his left hand he forms the karuṇā mudrā, which symbolizes compassion. I’m not sure why. I’ll continue my research.

**********

The 1860+ standing female figures on the walls of Angkor Wat are devatā. They were known by this appellation until around the 1960’s, when someone began calling them apsarā. “Apsarā” stuck.

I had learned many years ago from Preah Maha Vimaladhamma Pin-Sem Sirisuvanno (the Abbot of Wat Bo, Siem Reap, and one of the world’s foremost authorities on the Angkorian civilization) that the correct appellation is devatā.

They appeared to me to be temple and palace staff. Servants. I asked D. S. Sood of Archeological Survey of India, then the head structural engineer for the Ta Prohn temple (since retired), what he thought. He said yes, they were servants. “May I quote you on that?” I asked. “Yes!”

I interviewed Pra Ratana Visuk Sithong Heng, the second-highest-ranking Cambodian monk in the United States, in 2024. And I mentioned how grateful I was to Preah Maha Pin-Sem for telling me all those years ago that the 1860+ standing female figures on the walls of Angkor Wat are devatā.

“Oh,” he said. “The servants in the royal palace in Phnom Penh are called devatā to this day.”

Thank you, Pra Ratana Visuk Sithong Heng, for helping to set the record straight.

**********

Another once-in-a-lifetime discovery, this one from just south of Siem Reap town at Wat Athvea.

In Angkor Wat, Sūryavarman II wanted to show us how well his court lived - from the royals right down to the servants. Similarly, the designer of the bas relief at Wat Athvea wanted to show us how the Ashavali sashes were worn.

The Ashavali sash was threaded through a slit in the top of the skirt. The figure on the left is the only one I’ve ever found where you can see the slit. Sappho Marchal found one at Angkor Wat in the 1920’s, but thought that what was threaded through the slit was not a sash, but a narrow strip attached to the skirt. In the days before commercial air travel and the Internet, she would have no way of knowing of Ashavali sashes.

One end of the sash splashed out over the side of the skirt. The other end spilled over the front of the skirt, so that the patterns could be seen clearly. Look at the figure on the left, at the sash on her right - these Ashavali patterns are still made in Gujarat today. Pull up an Ashavali sari company on the Internet and you can see some of them. The swirling pattern in the widest band, a flowering vine, is still very popular.

The discovery of the slit in the skirt was two-fold. I had wondered why the devatā at Angkor Wat appear, at first glance, to be striking the Indian yakshī pose. One hand up in the air (Indian yakshī in this pose are reaching up into a tree to make it burst into flower - they’re earth spirits), and one hand in front of the hip.

Here you can see why, at Angkor, there was a hand over the hip - to hide the slit in the skirt. The figure on the left is not hiding the slit, the figure on the right is.

At Angkor Wat the hand up in the air is showing off one end of the Ashavali sash. Remember - this was some of the first brocade made anywhere in the world. Very expensive. And it was new at Angkor.

I believe what we see at Angkor Wat is the devatā getting ready to participate in the Procession of the Queens. Doing their hair, looking in mirrors, talking excitedly with their friends. But remember - they were servants. The figure on the left reveals that the sash was separate from the skirt. I think the sashes were issued to the devatā right before the procession, and that they had to return them to the royal treasury after the pūjā.

In the scene over the Procession of the Queens in Angkor Wat we see Sūryavarman II and his courtiers. A few of the courtiers are wearing an Ashavali sash across the chest, further evidence that the sash was separate, not attached to the garment. In the photo below, look above and below the courtier’s left hand to see the crossed sash. You can see the end of the sash over his right shoulder.

**********

OK, now we go way back. We see seven groups of women at Angkor Wat. When I began my research, only two had been correctly identified.

First, I listed them. And then, I ranked them. By what we see them wearing, what we see them doing, and their proximity to the other groups.

The twenty-four women guarding the inner sanctum on the highest level of Angkor Wat have more silk in their clothing than even the queens. And their jewelry, and their long chain belts, are the most ornate. Some have metal hair ornaments that defy gravity by floating ethereally in the air. I identified them linguistically, as explained in Through the Eyes of a Queen. They’re benevolent yakshī - gentle earth spirits, semi-divine. They’re #1 in status.

The figures actively dancing what looks like the Indian temple dance Bharatnatyam had already been identified. They can be seen along the front wall of the western entrance, and on pillars inside the temple. They’re dancing on lotus that would sink under their weight if they were mortal (they’re suspended in the air, so there is no weight on the lotus). These are the dancing apsarā. They’re #2. Apsarā are celestial beings. This is the Sanskrit definition (from the Sir Monier Monier-Williams dictionary): “‘going in the waters or between the waters of the clouds,’ a class of female divinities (sometimes called ‘nymphs;’ they inhabit the sky, but often visit the earth; they are the wives of the Gandharvas… and have the faculty of changing their shapes at will; they are fond of the water; one of their number, Rambha, is said to have been produced at the churning of the ocean).” At Angkor, if a female figure is not doing something super-human (like floating in the air, or dancing in the air), she is not an apsarā.

Likewise the apsarā floating up from the Sea of Milk in the Eastern Gallery had already been identified. They’re #3.

The five queens in the Southern Gallery were identified for me by D. S. Sood, the head structural engineer of the Ta Prohm temple until his retirement (Archeological Survey of India). I knew he was right, because Sūryavarman II would not have entrusted the royal Vishnu pūjā to anyone other than his queens. They’re #4 in status, because they’re mortal.

The six women following the queens in carts were the most difficult to identify - it was months before I was able to make out the wheel of one of the carts through 900 years of erosion. Their small, delicate feet indicate that they were drawn from the Angkorian elite, the sixth holds what appears to be an emblem of rank, they’re in close physical proximity to the queens (and probably the same caste group, Kshatriya), and they’re the only people in the Procession of the Queens other than the queens themselves who are not walking. Zhou Daguan, a Chinese emissary to Angkor a century and a half later, observed several royal processions and identified one group as “servants in carts”. These six women may be that group. But think about this, too. Because Angkor was at war with the Cham and the Dai Viet, security was a major concern. These women are probably carrying food to the pūjā. So easy to poison it - they were trusted not to. They’re #5 in status.

We see thirty-two men and women carrying vessels of food and drink to the pūjā. Also trusted not to poison it. And also in close proximity to the queens, probably the same caste group. Zhou Daguan wrote that in the processions he saw these vessels were silver and gold, so these 32 people were entrusted with royal treasures. They’re #6 in status.

Now we get to the 1860+ standing women on the walls outside the galleries. I noted that all have the ponderous feet of working women (not the lithe feet of dancers), and in fact many are seen doing the tasks of servants. They’re mistakenly called apsarā today. But I had learned from the second-highest-ranking monk in Cambodia (the abbot of Wat Bo), and from the book published by Sappho Marchal in 1927, that they’re devatā. I also identified them linguistically, as explained in Through the Eyes of a Queen. They’re temple and palace staff. The lowest in status, #7. The great irony is that they’ve been thought to be goddesses, or dancers, or celestials of some sort or another. Some scholars have based their assumption on the complexity of the coiffures. In fact, the coiffures were astonishingly easy to create - knot the hair on top of the head, set the crown in place, then insert flowers behind the crown (these flowers have been mistaken for braids). We see devatā only on Sūryavarman II’s temples, and only those at Angkor Wat look like they’re getting ready for something… I believe they were getting ready to participate in the royal Vishnu puja.