Chorabab Pattern “Bank”

Chorabab brocade is dying out in Cambodia very quickly. There are many reasons for this. In 2023 I wrote a comprehensive report for the Cambodian government and the office of the King outlining the complex problems causing the decline, and proposing solutions.*

But there is one problem for which I could not find a solution. And that is climate change. The area where chorabab is made - eight villages in Ksach Kandal District, across the Mekong from the north side of Phnom Penh - is being hit doubly hard. Chorabab artisans are experiencing the climate change that the rest of the country is facing. But on top of that, their fishing and farming villages are being swallowed by the urban sprawl of 21st-century Phnom Penh. Trees are coming down for new buildings - and those buildings are cement. Old roads are being paved, and new ones are going in. And the wildlife that keeps the mosquito population in check - bats, small birds, spiders, frogs, fish, geckos, lizards - is beginning to disappear. More mosquitoes, more disease.

I came up with the idea of creating a “bank” of traditional chorabab patterns outside of Cambodia, in a colder climate. I presented my proposal to the Victoria and Albert, was awarded a grant, and then got buy-in from a world-famous museum. Then, I set to work. Because not only do I want to save chorabab patterns from extinction, I want to create a model that others can use to document dying textile traditions in their countries.

The idea is simple, the scale is small (but expandable), and the expense is minimal. Collect 12 one-meter X one-meter pieces of the “endangered” textile in the loveliest of the traditional patterns still made, in colors that will complement each other when they’re exhibited together. Identify each pattern so that the museum can write the labels for exhibiting the pieces. And give them documentation of the technology used to create the patterns.

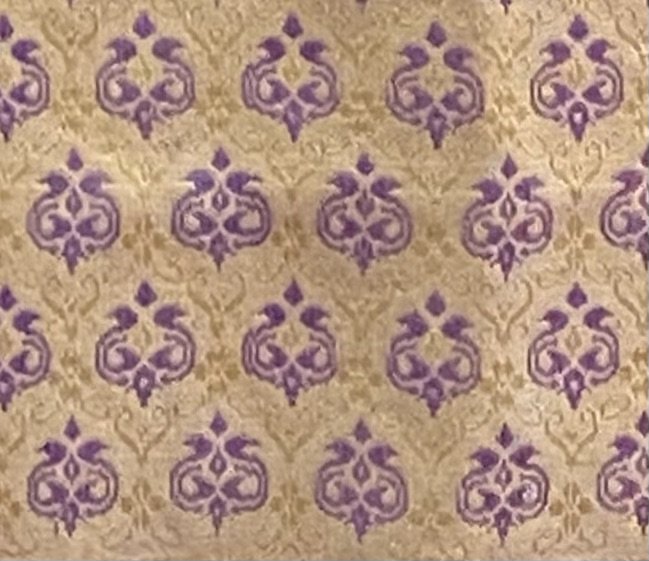

Here are a few of the patterns in the pieces I’ve collected for the chorabab “bank”. From top left, Rumduol Flowers, Chatting Peacocks, Classic “Chan Flowers”, abstract patterns, Pomegranates, the Emblem of the Cambodian Royal House, Hands Pressed Together in an Offering Position, variation on Classic “Chan Flowers”, Khmer Theravada Buddhist Temples, an abstract pattern (there are flaws in this piece, but they can’t be seen when the fabric is viewed in an exhibition setting), Millipedes, Eight-petaled Flowers (at the bottom of the photo). Some of these patterns are Khmer, some came from India centuries ago.

Some chorabab patterns are of historical importance. H. R. H. Norodom Sihamoni wore the Emblem of the Cambodian Royal House for his coronation in 2004. Some, such as the Classic “Chan Flower” pattern, were worn by the Angkorian elite; through nine centuries of erosion, we can still see them on the walls of Angkor Wat (top pattern, below left).

Let me illustrate the value of a pattern “bank”. I wanted a piece for the museum that included the bottom pattern in the photo below left, because we see Sūryavarman II’s fourth queen wearing this pattern in the Royal Procession in the Southern Gallery. It was still made in Cambodia until recently, but has fallen out of fashion.

The chorabab producer tried to replicate it for me, but couldn’t - she came up with the pattern in the middle. Why could she not replicate the fourth queen’s pattern? Because no one had saved a piece of the actual fabric. Her pattern setter could have set the pattern up for the weaver if she had had a fabric sample to work from, but she couldn’t do it by looking at a photograph of the pattern. In the photo on the right you see the Indian version of the pattern (Ashavali brocade, bottom row). It can be replicated because someone did save a piece of the actual fabric.

Below are the pattern setters who set up the looms for the weavers to make the pieces for the chorabab pattern “bank”. From left, Srey Neith Lok and Srey Pouv Boot. Srey Pouv is counting warp threads using a porcupine quill, which you see in her right hand (between her thumb and her index finger).

Below are the weavers who made the pieces for the pattern “bank”. From left, Seiha Lok, Heang Vorn, (name forthcoming) and (name forthcoming).

* I identified the problems facing chorabab artisans today with the assistance of two sixth-generation producers, Makara Lok of Nara Silk and Seiha Lok of Seiha Silk. Both are designers, dyers and weavers in addition to being producers. Makara Lok is unique in that she can also make ikat (she studied with Kikuo Morimoto for four years). Seiha Lok is unique in that he has a university degree. None of the problems we identified are in any way related to the Khmer Rouge genocide of 1975 to 1979, or to the ten-year Vietnamese occupation that followed. Makara Lok, as of 2025, has 48 weavers in her employ; they have all chosen weaving at home over factory jobs, which are readily available to them (i.e., losing chorabab weavers to factory jobs is not an issue for her business). The list of the 29 problems facing chorabab production today is on the Sustainability tab of this website. It could be used as a checklist by anyone trying to identify the problems facing another dying textile tradition.